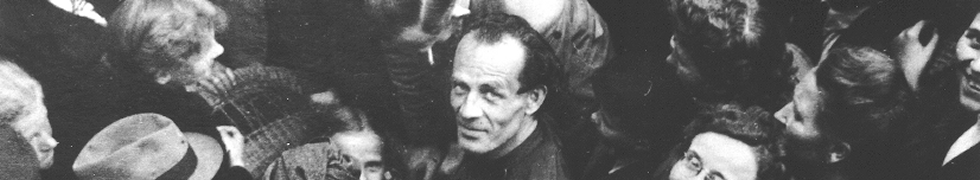

Bruno Gröning (1906-1959)

An extraordinary, yet controversial person

In 1949, the name Bruno Gröning became a household word in Germany overnight. Reports about him appeared in the press, in newsreels and on the radio. Events surrounding the “Miracle Doctor” as he soon came to be called, kept the whole country in suspense. A film was made about him, scientific investigation committees were set up and government authorities at the highest level gave the Bruno Gröning matter their attention. The Minister for Social Affairs in North-Rhine-Westphalia had him prosecuted for violating the Non-Medical Practitioners Act, while the Minister President of Bavaria declared that one could not let such an “exceptional occurrence” as Gröning be squandered because of a few legalities on paper. The Bavarian Interior Ministry described his work as “a labor of love, free of charge”.

In 1949, the name Bruno Gröning became a household word in Germany overnight. Reports about him appeared in the press, in newsreels and on the radio. Events surrounding the “Miracle Doctor” as he soon came to be called, kept the whole country in suspense. A film was made about him, scientific investigation committees were set up and government authorities at the highest level gave the Bruno Gröning matter their attention. The Minister for Social Affairs in North-Rhine-Westphalia had him prosecuted for violating the Non-Medical Practitioners Act, while the Minister President of Bavaria declared that one could not let such an “exceptional occurrence” as Gröning be squandered because of a few legalities on paper. The Bavarian Interior Ministry described his work as “a labor of love, free of charge”.

The case was intensely and controversially debated at all levels of society. Emotions ran high. Clergymen, physicians, journalists, politicians and psychologists were all talking about Gröning. Some considered his miraculous healings a gift of grace from a Higher Power; others believed he was a charlatan. But the healings were fact, confirmed by medical examinations.

Worldwide interest in an unassuming worker

Bruno Gröning, born in 1906 in Gdansk, was an unassuming worker who relocated to Western Germany as a refugee after World War II. Before the war, he had worked in various capacities: as a carpenter, a factory and dock laborer. Then, suddenly, he was the center of public attention. The news of his miraculous healings spread all around the world. Sick people, petitions and proposals came from every country. Tens of thousands of people made the pilgrimage to the places where he was active. A revolution in medicine was on the horizon.

In the strangle-hold of prohibitions, court cases and profiteering assistants

But counter-forces were at work. They did their utmost to foil Gröning’s activities. He was dogged by court cases and healing prohibitions. All efforts to incorporate his work into the existing social structure failed. On the one hand, there was the resistance of those in authority at various levels of the social order, and on the other, the his assistants’ greed for financial profit. When he died in Paris in 1959, the last court case was well under way. The proceedings were halted and a final verdict was never pronounced. But many questions remained unanswered.